FINANCE

What’s Your Relationship with Conversational AI?

We all have a pretty good grasp of the kinds of qualities we search for in friends. We look for people who are loyal, supportive, good company and forgiving, but are these the same qualities we want from our AIs and intelligent personal assistants? Daniel Davies explores the relationships being built between humans and intelligent machines

When we think about artificially intelligent machines existing around us, we tend to anthropomorphise them. We imagine inviting these AIs into our homes, our offices, even our bedrooms. Right now, it’s only really our friends and family that we have such intimate relationships with, but the relationships being built between humans and intelligent machines appear as familiar.

Before we have that awkward ‘how serious is this relationship’ conversation with our intelligent assistants, though, there are some pretty fundamental questions that we need to resolve. Like, does their speech need to resemble humans? Is there value in that, or are we more comfortable keeping humans and machines in distinct and separate categories?

If we are more comfortable with machines speaking like humans, can we make them understand the colloquialisms and meanderings we drop into everyday conversations? Or do we need to develop a formal way of speaking to AIs?

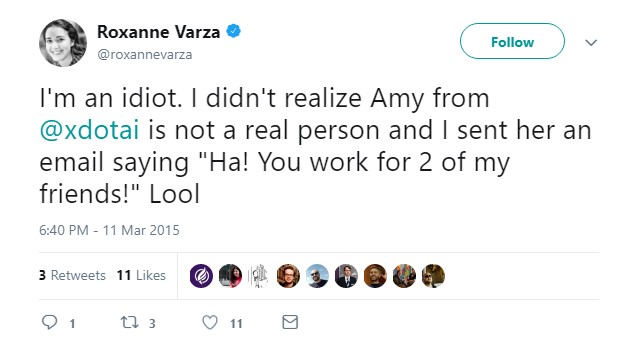

For the past 4 years, Dennis Mortensen and 150 of his friends have been holed up in Manhattan, building intelligent agents that can schedule meetings for you. But Amy and Andrew Ingram – the personal assistants Mortensen’s company, x.ai, came up with – do more than just figure out appropriate dates for you and your workmates to get together. They take over your diary, directly liaising with colleagues to arrange or sympathetically rearrange meetings.

To give everyone access to a personal assistant that would previously have been reserved for members of the C-suite – a process which x.ai calls “democratising the calendar” – Mortensen and his team have had to deal will some of the issues that arise when humans expect to have the same kinds of intimate relationships with machines that they have with humans.

“People are crazy,” said Mortensen during a Q&A at Web Summit. “It would just be great if they were not crazy and could tell a machine: ‘let's meet up on Wednesday, 13:00 hours EST on 200 Broadway, 10005 New York, New York’. This is not how we talk.

"You'll say all sorts of things: ‘let's do 1 o'clock because I have that PTA meeting with my kids at 2 o'clock, so I might not be finished until 3, but we can obviously do shortly thereafter’. That little PTA story about you and your kids doesn't matter, but that's how we talk and we have to exist in that universe, and that makes it complex.”

What are these relationships with AIs?

“We certainly see relationships being created with our agents,” said Mortensen. “We can talk about what kind of relationships, but they're certainly existing at some level.

“I bloody work there, but I still start out most of my requests with 'Amy, would you be so kind'.”

Humans developing intimate relationships with machines is nothing new. Anyone around in the mid-90s who saw how fixated children were with their tamagotchis can attest to that, but there was never any suggestion that a tamagotchi was anything other than a virtual pet. The stories Mortensen tells about people’s reactions to Amy and Andrew, however, point towards the development of different, more familiar interactions.

“In 11% of all the meetings we set up, hundreds of thousands of meetings, at least one of the emails in that dialogue will have no other intent than gratitude, as in someone who knew this was a machine went back to it to say 'thank you very much, really appreciate you setting this up on Friday this week’,” said Mortensen.

“I bloody work there, but I still start out most of my requests with 'Amy, would you be so kind'”

These people are showing gratitude to a piece of software, which is a new phenomenon. But will we expect this to be the norm going forward? Will we expect our intelligent assistants to be able to pass the Turing Test and convince us of their consciousness?

“None of us really have much of a relationship with, say, Photoshop. If I need to work on an image, I’ll open up the application, use it and be happy,” said Mortensen.

“But as soon as you move to the conversation where within the UI, you can have these agents, whatever their job might be, converse with you in natural language, the ability to imagine and really inject emotion into these agents just becomes very easy. And the real question is: is it now a game of whether I can fool you into believing that this is a human?

“I'm not so sure that I believe that that's a game worth playing. But that doesn't mean that I don't think there's value in applying levels of human emotion into that dialogue. Not to fool you, but because that holds value in the dialogue.”

Real or not, AIs are stoking our emotions

When Mortensen talks about injecting valuable emotions into the dialogue, what he means is using an emotion like sensitivity, not to trick a recipient but to benefit the conversation. He gives the example: if someone couldn’t make an appointment three times, then any reasonable person may think they’re being snubbed. A machine wouldn’t realise that, but a human may handle the rescheduling with increasing delicacy.

“Amy obviously has no real idea, and she can loop this seventeen times over and not care,” said Mortensen. “You care though, as though Dennis was kind of a nice guy, now I think he's a bit of an asshole, and you need to kind of allow yourself to figure out: do I even want that meeting?

“What we have seen is if Amy recognises the fact that this is slightly unfortunate and starts out with a simple way of saying that, to a full-on apology on the third retry, that level of emotion from where she also knows this is unfortunate increases the probability of the meeting being kept intact.

“Think about that: people know that this is a machine, they know the emotion we portray is not real, but just by the fact that it's visualised, has them saying 'perhaps Dennis isn't an asshole, he's just busy'.”

“I'd much rather we tell people upfront 'hey this is a machine', but we do the job so well that in the end you say 'thanks, Amy'”

Despite not wanting to inject emotions into intelligent machines to trick users, the presence of these emotions inadvertently stokes emotional reactions from people.

X.ai has also given its intelligent agents the ability to relay all the conversations it has with third parties back to its boss, which reveals just how strong attachments to conversational machines have become, with people sometimes seemingly preferring them to other people.

“If you were the boss of Amy you could see what she talks about to all of your guests, so you could just jump in and ask her 'hey what did you and John talk about?',” said Mortensen.

“She'll send that back and you can see the whole dialogue. People use that as a backdrop to 'I think John is a little bit rude'. As in, I don't think I like John that much actually, in the way that he treated Amy, even though I don't care whether you triple click on any icon in Photoshop.

“You can click all you want. I don't really care, but somehow there's a different relationship here where 'I don't like the way he talked to Amy'.”

For x.ai, even though the line is blurring, there’s no need to pretend that these relationships are anything more that of a human to a machine. “I'd much rather we tell people upfront 'hey this is a machine', but we do the job so well that in the end you say 'thanks, Amy',” said Mortensen.

But given that real relationships between humans and machines are beginning to blossom with the earliest iterations of conversational AIs, it’s no wonder that we can see these machines becoming increasingly involved in our lives.