Technology

Could Visual Search Have Stopped the Manchester Bomber?

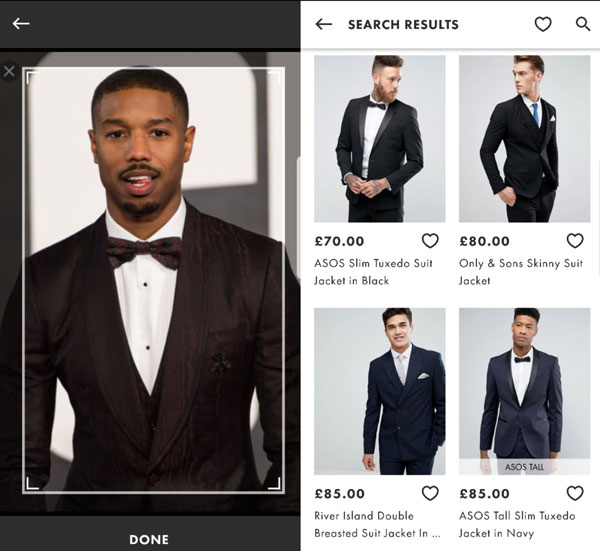

If you use ASOS’ app you may have already experienced visual search and found clothes you like based on your photographs, but the technology can do so much more. Daniel Davies explores how visual search could replace radiologists in hospitals or even identify terror suspects

What can you do with visual search? If you think the answer to that question is: you can use it to look for clothes based on a photo, then you’re right, but you’re also seriously underestimating the technology.

Because the artificial intelligence-powered tool can do much more than just find clothes that you’ve taken a snap of, as it does on ASOS’ app or the Kim Kardashian-backed ScreenShop. It could be used to prevent terrorist attacks, or if the workload in our overburdened health systems becomes too much it could be used to examine X-rays, standing in for human radiologists. Because visual search basically works by recognising objects, it could even be the technology that puts driverless cars on the road by recognising road signs.

But that isn’t to say that visual search is finished with retail yet. Imagine if live TV became shoppable; imagine if you were watching your favourite television programmes and you could buy the clothes, furniture, transport, or any of the adornments that bring characters to life. Imagine if as an advertiser you could let customers buy your products and services during their normal scheduled programming.

“With AI there're loads of terms,” says Alastair Harvey, chief solutions officer for the vision AI firm Cortexica. “Everyone's talked about deep learning, image recognition, machine learning. Most people actually apply those terms incorrectly, and of course because everyone's hearing about AI they just put everything together. They think it's the same. So visual search is one component of what we do, and the bit that comes before the visual search is probably best described as object recognition.

“You also have facial recognition...[which is] searching for one face across a data set. That's a visual search, but it's specifically facial recognition, [what we do] is more about object recognition, take a photo...and then you can search for it.”

Identifying the Manchester bomber

Last May, 22-year-old Salman Abedi detonated a home-made bomb in the foyer of the UK’s Manchester Arena as children and parents were leaving an Ariana Grande concert.

Having only been arrested for minor offences back in 2012, Abedi wasn’t being tracked by counter-terrorism officers, and even though he had reportedly expressed extremist views, Abedi had slipped through the cracks of the UK government’s Prevent scheme, which aims to identify people at risk of being drawn into terrorism.

While visual search is no replacement for education or a well thought out anti-terror programme, it could have acted like a safety net and drawn attention to Abedi’s suspicious behaviour, and potentially helped law enforcement identify Abedi before he was able to carry out his inhuman act.

“Action recognition is the key bit here – so am I scratching my ear or am I going to make a fist; am I running to something or am I running away from something”

“You can put the ability to recognise what might be happening as a set of actions. Action recognition is the key bit here – so am I scratching my ear or am I going to make a fist; am I running to something or am I running away from something; if everybody is flowing that way, why am I going the other way; I had a bag, now I don't have a bag,” says Harvey.

“If you take the horror that was the Manchester Arena scenario...unless you're monitoring at the time, which of course human error and if you turn away it's done, whereas a computer doesn't turn away. They have retrospectively gone over the footage to try and find him and try and map where he was and what he was doing, and there are obvious things. People were going one way, he was going the other way. He had a bag and he was moving through. You can train systems to [spot specific behaviours].

“None of this is facial recognition, so it's all about how we move...so that training set from a security point of view is huge.”

Stills of Salman Abedi prior to the attack. Image courtesy of Greater Manchester Police

Facial recognition versus visual search

When people talk about using visual AI for security, they’re usually referring to facial recognition, and recently a number of authoritarian governments have reportedly been exploring using the technology to identify wrongdoing (I’ve seen reports of this technology being used or about to be used in places like China and Dubai).

Despite what these nations think, facial recognition may not be as successful as object recognition – which is the branch of visual AI Cortexica specialise in – when it comes to identifying suspects, especially when those suspects, like in the case of Salman Abedi, aren’t actively being searched for by authorities. But even if they are, as Harvey explains, evading facial recognition technology doesn’t require a master of disguise.

“Facial recognition is very difficult,” says Harvey. “You take your glasses of it won't know you. You put a veil on, you put a hat on, you put something on that changes [the way you look]. It's really tricky. Whereas you can't do that with how you move because you move how you move.”

Harvey goes on to explain that facial recognition works well on a micro level because matching “one face against one picture” is “pretty simple”. But on a macro level, picking out one face, which can be altered or covered, out of thousands is a much more difficult task.

Even using object recognition, it’s still difficult to pick out one behaviour or act from thousands and hope that the AI has seen it before.

“You take your glasses of it won't know you. You put a veil on, you put a hat on, you put something on that changes [the way you look]. It's really tricky”

Currently, most object recognition works by sifting through huge data sets and ‘learning’ to recognise repetitive actions. If the AI hasn’t seen something before though, it won’t recognise it and won’t flag it as a concern. As Harvey explains, where Cortexica’s technology is different is that it has the ability to look at a scene before verifying whether there’s anything to worry about and comparing that to a data set, in essence working backwards or learning on the job.

“It's about replicating how we see, so that's light, shade, depth, colour, shape and everything that we're doing subconsciously, it'll replicate that,” says Harvey.

“The true AI with deep learning and things is about repetitive actions and recognition through huge training sets, so if it hasn't seen something it won't recognise it. These companies that specialise in that have tens of thousands of objects. Our technology, we can do that, it's part of what we can have, but...we're able to recognise and search for something that hasn't been trained for because we [can] visually analyse that and then find it in a data set.”

Object recognition replacing radiologists

In December 2017, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) found that the Queen Alexandra Hospital in Portsmouth had caused “significant harm” to three of its patients because it failed to spot cases of lung cancer, having not checked patients' chest X-rays properly.

The CQC inspectors also found the hospital had a backlog of 23,000 chest X-rays, and junior doctors had complained about being asked to carry out specialist radiology work without the appropriate training.

Because the work radiologists do is image-based, visual search and object recognition could be used to take the burden away from understaffed health services.

“The good thing about vision and any AI application is it removes the need for... knowledge, language or expertise because it's trained to do the same thing constantly and learn as well; it teaches itself,” says Harvey.

“This is big area, we don't specialise in it at all, but we can do it technically,” he adds. “That includes detecting cancers from X-rays or even down to anomalies in cells because 'this is a data set of healthy cells, there's a data set of bad cells track them and find them', so we can do that.”

“To help time strapped, cash strapped doctors process images, whatever they are, the technology's there but it needs to be trained”

Using AI to analyse X-rays could solve a massive problem, but because of the sensitive nature of the data an AI in healthcare would have to deal with, it’s not as simple as just allowing the tech to go to work.

“You would need to have the training sets, so you've got to have a lot of X-rays with the outcomes of what those X-rays are: all clear, two inclusion, one inclusion, not cancerous, all of those types of things. So to actually get access to that through a system you've got to do the whole data stuff, so you can't just go into a hospital. There's that privacy, which is absolutely right, but that needs to be removed...and then it could happen,” says Harvey.

Harvey suggests implementing a system whereby patients can allow their data to be used, under strict government control.

“You don't want loads of companies just going off and doing this randomly with people's data, like they do with apps once I agree terms and conditions, but if there was essential government data training sets, anonymised, that companies could use, or we would use, it could be achieved,” says Harvey.

“If the technology, which it can do, could remove 60% of that first judgement, which meant that they had to provide their proper doctor the final seal of approval on the top 40%, that's a 60% saving in time,” he adds. “To help time strapped, cash strapped doctors process images, whatever they are, the technology's there but it needs to be trained and that needs to have a dataset, so if somebody got that and said to us 'can you do it?' We'd do it.”

Visual search goes back to retail

Cortexica’s background is in retail, and it’s in retail that visual search is making the most impact, for now at least. The company has already worked with one of Europe’s major shopping centre investors, Hammerson, on an app that can be used in Brent Cross shopping centre in the UK.

The Style Seeker app, Harvey explains, uses the collated products from each individual store within the shopping centre and allows shoppers to“take a photograph of a jumper, and it'll come up with either that exact jumper or similar jumpers by shape or colour or whatever.”

“When you're in it you may find a brilliant aspirational £1,000 pair of Gucci shoes; you can use the shopping centre app take a photograph and find that there is something similar at Ted Baker for £200,” Harvey adds.

The app is an example of “click and brick”, so once shoppers have decided on a purchase and made their way to the shopping centre, the app will help them find exactly where it is, which has increased footfall and dwell time in the centre.

“Big companies who own the bricks, they’re massively behind that and we're about to roll it out in France as well,” says Harvey.

“We can make live TV shoppable or interactive, so you could be watching a programme, a DIY something or other and you could see the drill and press the drill and it comes up”

Considering what visual search and object recognition can do, though, the Brent Cross app is a pretty traditional use of the technology.

It’s what Cortexica has coming next that may revolutionise retail and advertising.

Who watches adverts anymore? So foreign has the experience become, it’s a really strange experience to be in a cinema nowadays and be forced to sit through them. The explosion of catch-up and on-demand services such as Netflix, the rise in the recording of shows and the skipping of ads, and a decline in viewing on traditional TV sets by younger viewers has led advertisers to look beyond the traditional, 30-second commercial.

One of the ways advertisers have attempted to capture modern audiences’ attentions is through product placement. The next logical step is to have those products purchasable when we see them on screen. And that’s where visual search is heading next.

“If you're watching as most people are on their phones, or a tablet, we can make live TV shoppable or interactive, so you could be watching a programme, a DIY something or other and you could see the drill and press the drill and it comes up, so there's an inventory behind it selling stuff,” says Harvey.

“There's a popular singing competition on live TV. If you like 'Chantelle's' dress and she's banging out a Whitney number, I could click on it and it would search. That's commercial... and that technology is now available. We can do that, with limits. It can only do what it's been trained to do.”

If you’ve used ASOS’ app or the Cortexica-designed Style Seeker then you’ll have had a glimpse into what visual search is capable of. But in healthcare, security as well as retail we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of what visual search can do.

“We're trying to grow fast enough to keep up with it,” says Harvey. “We don't have the chequebook that Facebook has to just go in and hire 5000 people, but it'll only go as fast as the people who make it.”

Image courtesy of ASOS